It is becoming increasingly important that Boards, their executives and officers understand, develop and play a critical role in how an organisation governs its Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues – an area which is continually evolving.

Below is an excerpt from a recent webinar on this very topic, with part 1 of the series focusing on ESG activism and directors' duties.

ESG is gaining momentum

ESG is not new. It's been here for a while and it's certainly gaining some momentum.

While it's a little bit debated, the position is that it began in the 60s when investors really started looking towards shunning stocks that were related to things like tobacco production or indiscriminate use of pesticides such as DDT or were involved or supporters of the South African apartheid regime.

This trend has really continued and strengthened in the decades that have followed.

Source: Researchgate

Source: Researchgate

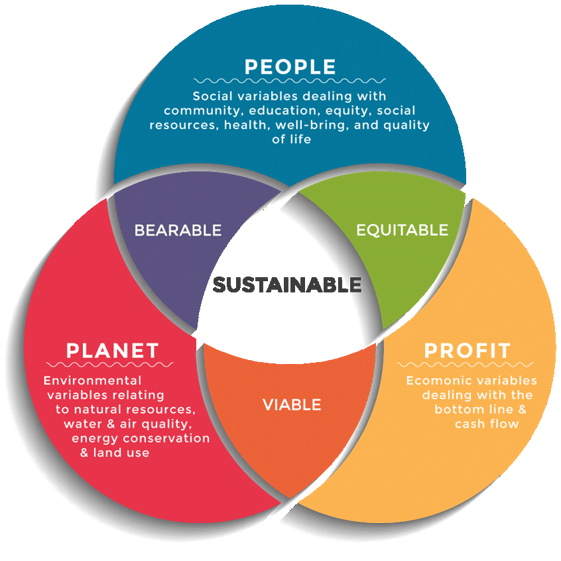

You might recall back in the 90s when the concept of the triple bottom line was born, and its purpose was really to help transform the idea of what success looks like. And importantly, how it was measured beyond all financial metrics and instead adopting socially and environmentally responsible behaviors that could be balanced with your economic goals.

The term ESG as we know it today, was coined in the mid 2000s following a report called Who Cares Wins - sounds a bit like a game show, but it's not - and from there it's become a global phenomenon and a force that we can no longer afford to ignore.

We've had some forewarning. We've had some sort of time to prepare for where we are now, something we have to do and a question that often comes up is ‘does it actually make sense economically?’. And this will be particularly relevant for those operating in sectors that perhaps have razor thin margins already.

The overwhelming weight of accumulated research finds that companies that pay attention to ESG concerns don't experience any drag on value creation - in fact, it's quite the opposite. The strong ESG proposition has actually been shown to lead to higher equity returns and has multiple positive links to cash flow.

ESG activism

What is ESG activism? It's essentially where people campaign for, or sometimes quite demandingly require a change or improved outcomes or transparent reporting on environmental, social and governance factors.

Activists can include people that aren't even your shareholders, such as not-for-profit groups. They can include hedge funds, super funds, fund managers, as well as your long-term investors and substantial shareholders.

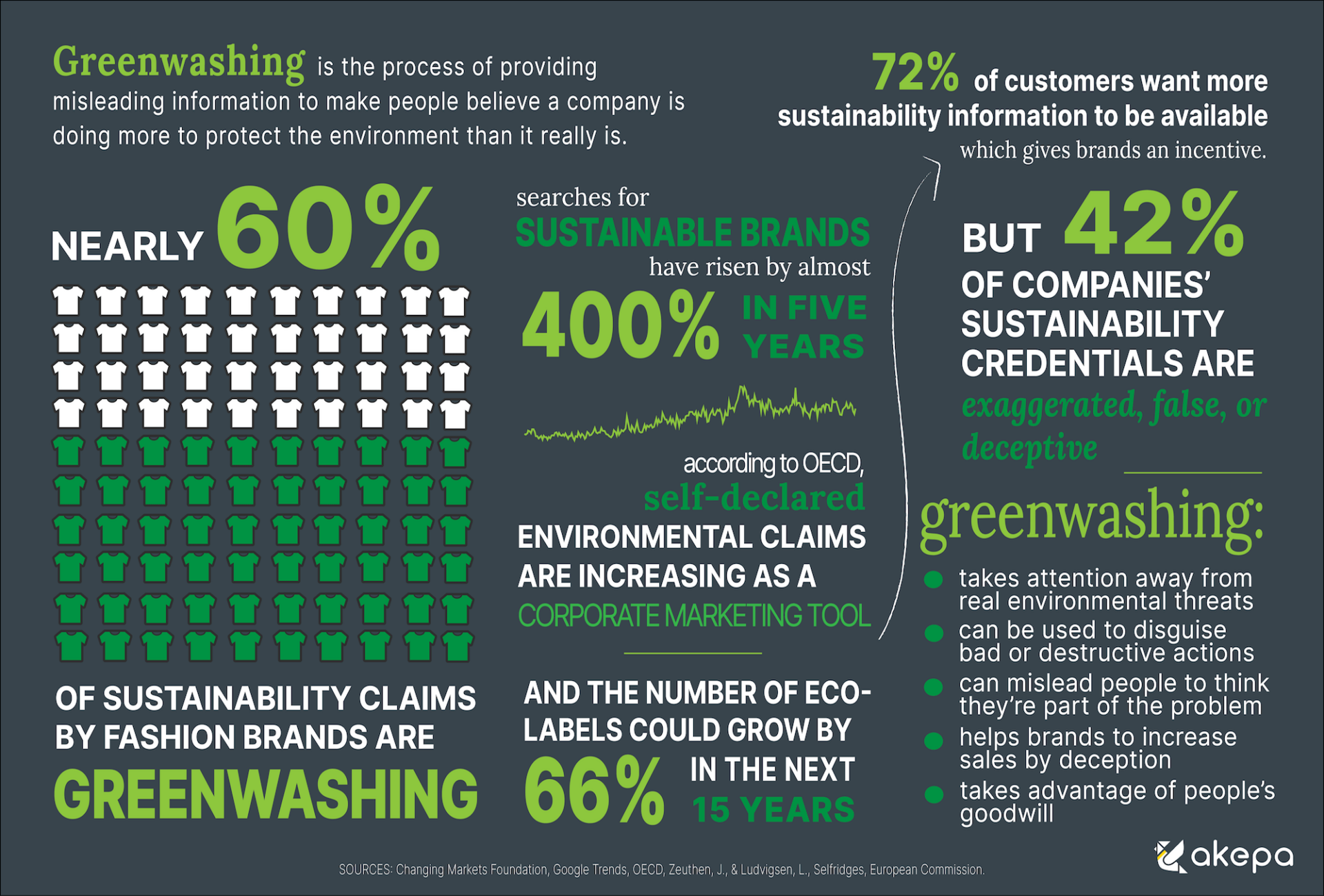

There's been a recent surge in ESG activism which has coincided at a time that we've seen increased scrutiny from regulators, in particular the ACCC and ASIC on greenwashing and other ESG issues.

Source: Akepa

Source: Akepa

Just earlier in October, the ACCC launched two internet sweeps which were designed at identifying misleading environmental and sustainability marketing claims as well as fatal misleading online business reviews and 200 company websites were reviewed in the sweep as part of a proactive approach on stamping out greenwashing.

Equally, ASIC said it is going to actively monitor the market for potential greenwashing and it's going to take enforcement action including court action where it identifies serious breaches.

You might have read in the media last week, ASIC actually put its money where its mouth was and took its first action for greenwashing against a company called Tlou Energy.

For those that didn't read up about it, Tlou has to pay more than $53,000 to comply with four infringement notices that ASIC issued relating to concerns that arose from just two ASX announcements, where ASIC asserted that those announcements do not have a reasonable basis for what they said or were factually incorrect.

The statements claimed that the electricity produced by Tlou would be carbon neutral and that they have the capability to generate certain quantities of electricity from solar power and that its gas to power project would be low emissions amongst other things.

We can see that the latest regulator activity just demonstrates the need for very careful verification of any material that you're putting publicly -whether that's an ASX announcement, a prospectus, product disclosure statement - you really need to be careful about not just the text of what you're putting up, but also any images.

What are the powers of these shareholder activists and the Corporations Act?

Thankfully the starting point is usually a chat or normally seek to have a private discussion with the board and seek to try and reach some sort of resolution.

When the activists feel that the board is not receptive to their concerns, they can - and often do - resort to increasingly aggressive or hostile methods. This could include speaking to the media, publishing websites and posting on social media platforms.

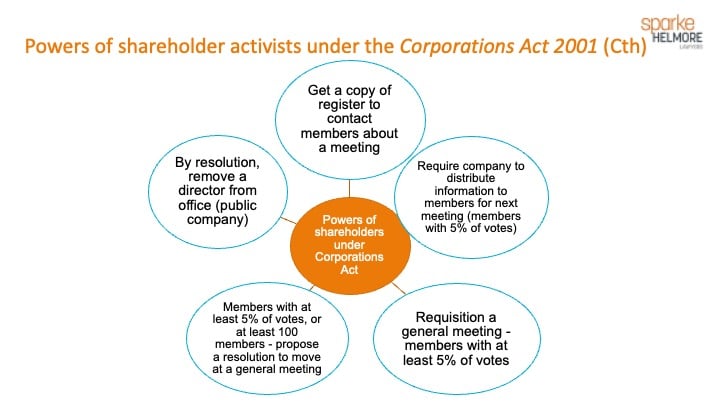

In Australia, the Corporations Act gives shareholders quite a bit of leverage in terms of things that they can demand.

You might be aware that shareholders are entitled to obtain a copy of the share register and to contact members about an upcoming meeting.

If they've got at least 5% of the votes, they can also require the company - at the company’s cost - to distribute information to members ahead of a meeting, which could include different things, but potentially, as an example, information about the removal of a director and essentially seek to influence how your shareholder base and your mum and dad investors are going to seek to vote a meeting.

Other more serious hostile approaches that are taken include:

- The ability of shareholders to requisition a meeting of the company

- the ability to give a company notice of a resolution that they propose to move at a general meeting

- Passing a resolution to remove a director from office

- Facilitating a board spill by utilising the annual ‘Two strikes you're out’ vote on pay for directors.

- Exercising their vote where one is required under the ASX listing rules or the Corporations Act to actually block a proposed transaction.

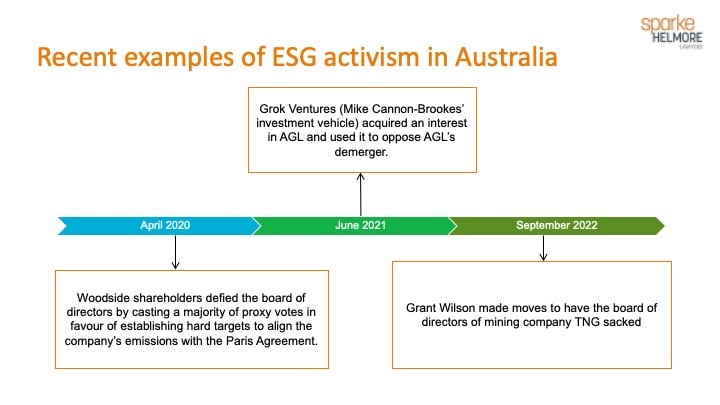

Recent examples of ESG activism in Australia

Here are a couple of recent examples that demonstrate the force of shareholder activism in Australia currently.

The first one relates to AGL Energy. You might be aware that they recently abandoned their plan to spin off their coal-fired power plants and its Chief Executive and Chair resigned after billionaire CEO Tech Company Atlassian and co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes persuaded the shareholders to oppose the demerger and this was, of course, after his own takeover bid, which was made in partnership with Brookfield, was rejected.

The Financial Times reported that Cannon-Brookes wanted to ensure that the entire AGL group’s financial balance sheet was used to fund the investment in renewables.

The Financial Times reported that Cannon-Brookes wanted to ensure that the entire AGL group’s financial balance sheet was used to fund the investment in renewables.

And this is important because it's reported that AGL accounts for somewhere between 8 and 10% of Australian emissions; and Cannon-Brookes said that more than half of all the AGL investors who actually voted to force the company to adopt Paris aligned targets at AGL’s previous AGM felt that the shareholder base had been ignored, so he upped the ante in blocking this transaction.

Another recent one relates to stoush between shareholders that took place in September this year between mining company TNG and Australian Financial Review columnist, Grant Wilson.

Wilson pushed to have the board of directors of TNG sacked on the basis that he thought they didn't know what they were doing, and they didn't have the requisite skills to take the company to develop its next phase of projects.

It was reported also that Grant’s view had been informed by his view that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had fundamentally changed his opinion on the role that should be played by Australia in the supply of minerals that are critical to defence, electric vehicles and also renewable energy transition.

Wilson sent a notice to the company, called a general meeting to remove two of the non-executive directors from the board - Elkington and Burton. He put a website up the same day that was publicly accessible and set out his case for change.

The meeting that he'd requisitioned was called with the resolutions for the removal of those shareholders but ultimately, when the AGM came to be, those resolutions didn't need to be put forward because the two non-executive directors whose resignation had been called for, tendered their resignations.

Both of these examples are good in showing the pressure that activists can successfully exert on companies to mandate change.

Directors’ Duties and role of the board

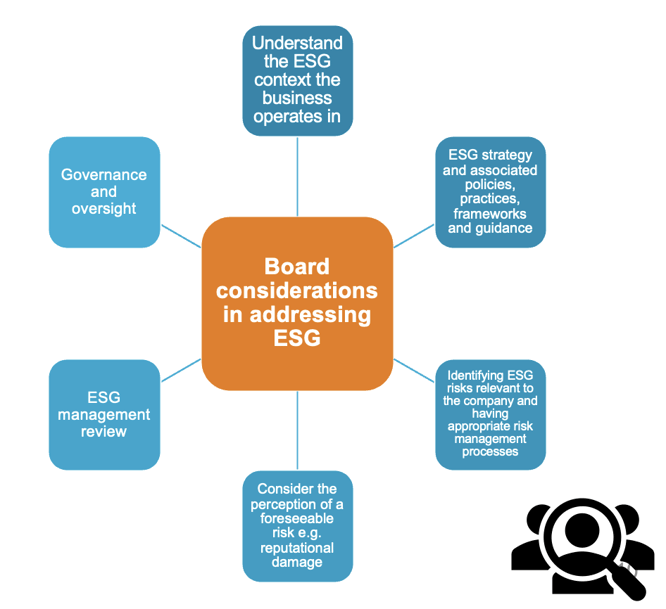

As board members, what's your role? What are your duties in relation to ESG?

As you’d well be aware, directors of Australian companies are bound by a number of fiduciary duties in general law and those are codified under the Corporations Act.

We're not going to do a rehash of those, but there are two that I would like to talk about in a little bit more detail as they've evolved and the way that they are interpreted has evolved as our position nationally on ESG continues to gain momentum.

The first one of those is the duty of care and diligence.

The first one of those is the duty of care and diligence.

As you know, directors must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they were director of a company, in the company circumstances and that they occupied the office held by and had the same responsibilities within the company as the director.

What constitutes a reasonable standard of care and diligence really depends upon the nature and extent of the foreseeable risk of harm.

In an ESG context, it’s not merely a matter of director saying that the relevant ESG issue is secondary to the profitability of the company and the return to shareholders.

This is well highlighted in a recent case, which is Cassimatis and ASIC, where the full Federal Court held that the duty of care and diligence is a matter of public concern. The presiding judge used the following example in his judgment:

The director makes a decision to commit a serious breach of law by intentionally discharging large volumes of toxic waste into the lake, for example. The director made this decision on the basis that the financial costs of avoiding the breach and safely discharging the waste would be far greater than the cost of a financial penalty under the relevant environmental regulation.

To recap, the director sides that it's cheaper to breach the law, discharge the toxic waste into the lake, and pay the penalty under the Environmental Legislation than to actually do the right thing, spend a little bit more money, avoid breach and to dispose of the waste responsibly.

The court found that the director may still be liable for breach of their statutory directors' duties. So, in this case, the duty of care and diligence, despite proving that the financial cost of a penalty for a serious breach of the law was less expensive and less costly to shareholders than complying with the law.

The case also confirmed that the director may still be in breach of their duty of care and diligence even if they don't actually breach any environmental legislation.

This really serves to demonstrate the breadth of statutory directors' duties and the way in which courts are now prepared to interpret them, notwithstanding that there's been no change to the duty itself.

The second statutory duty that I want to touch on is similar in the way that it's being interpreted more expansively, and that's the duty to act in good faith and in the best interest of the company.

Interestingly, this duty extends beyond maximising the profits of the company.

It's now generally accepted this duty extends to directors considering the interests of stakeholders which are not just shareholders, they include the general community, customers, employees and others.

And the justification for doing so is by reference to the long-term interests of the company, including its interest in avoiding reputational harm.

In the Banking Royal Commission, Commissioner Hayne noted that: "The duty is to pursue the long-term advantage of the enterprise. Pursuit of long-term advantage (as distinct from short term gains) entails preserving and enhancing the reputation of the enterprise as engaging in the activities it pursues efficiently, honestly and fairly."

In making decisions as a board and acting in the best interests of your company, you should consider the perception of a foreseeable risk of harm, which includes reputational harm and a broader set of stakeholders and industrial shareholders.

A lack of consideration or management of your ESG risks and opportunities - and pursuing a single-minded focus on profit - could amount to a breach of your directors' duties, as we've seen the way the courts will now look to interpret them. But they're also likely to impact negatively on your company's reputation and its market standing.

---

Stay tuned for part 2 of the series, where we discuss Modern Slavery and related trends.

----

Watch the full webinar on ESG here.

Related Articles

No more excuses for missing that contractual deadline

Contracts are lengthy documents containing business terms that you’ve agreed on, including milestones and key dates.

Building high-performance procurement teams

As talent shortages sweep through the construction industry and impact productivity, procurement is starting to feel the effects. Focusing on increasing the performance of your procurement team is important to delivering long-term outcomes.

Using Felix to store contracts - a holistic view of vendor relationships

You’ve found a vendor to engage, the Recommendation for Award has been created and approved (using Felix Vendor Management), and your organisation can successfully start the business relationship once the contract is signed.

Let's stay in touch

Get the monthly dose of supply chain, procurement and technology insights with the Felix newsletter.